Stefano Torelli’s 1777 portrait of the coronation of Catherine II, Tretiakov Gallery.

Historical overview and preface to the article published first on Pravoslavie.ru on 7 September 2015:

Some thoughts on the Russian monarchy, the implications of the Pauline Succession laws adapted by Emperor Paul I Petrovich Romanov after his 1796 accession upon his mother Empress Catherine II’s death, and the theological, mystagogical, and political significance of the coronation and anointing of Russian tsars and tsaritsas, emperors and empresses:

A brief overview of the eighteenth century imperial succession: from Peter I to Paul I

Emperor Paul’s succession laws in no ways completely legally barred or excluded women from inheriting the Imperial Throne; in practice they simply meant that every Russian monarch beginning with Paul himself was succeeded by his firstborn son, or, if he had no son, his closest male relative (i.e. brother). Prior to his issuing these decrees, Paul’s great-grandfather Peter I had broken with tradition, as he did so often, and declared that the reigning monarch could appoint whoever he or she wished as his or her chosen successor, including bypassing his or her own child/ren. Peter I himself had his own son and heir — the conservative, traditional, anti-Westernising Tsarevich Aleksey (Alexis), his son by his equally conservative and devout first and ex-wife Evdokia Lopoukhina — imprisoned on likely trumped- up treason charges and tortured (apparently only accidentally to death) in St Petersburg’s Peter and Paul Fortress. Ironically, despite changing the succession law from what had been a system of (unofficial) primogeniture to one of ‘whomsoever the monarch chooses’, Peter I himself died in 1725 without publicly naming his eldest surviving daughter or anyone else as his successor. A series of succession crises would characterize Russian Court politics until Catherine II’s death in November 1796.

Rather than his eldest but still young daughter Elizabeth Petrovna succeeding automatically, as would seem natural, leading imperial regiment officers, a coterie of Court notables, nobles, and leading churchmen agreed to give the Throne to Peter I’s Livonian-born widow, a barely literate peasant woman, former Lutheran, and former Army colonel’s mistress Marfa Skavronskaya (Catherine I) as sole monarch. Russia’s first Empress regnant Catherine I died after reigning for only two years, and, again, rather than her and Peter I’s daughter succeeding her as Empress, another Court coterie (dominated this time by conservatives) chose Peter I’s young grandson — son of the murdered, conservative Tsarevich Aleksey — to be monarch as Peter II in 1727. Conservative and devout like his father, and somewhat opposed to his grandfather’s forced Westernisation policies, Peter II moved the imperial court back to the more traditional, staunchly Orthodox ‘old capital’ of Moscow. He died mysteriously after only three years, again leaving no will just like his two predecessors.

After Peter II’s unexpected 1730 death, rather than acclaim as empress his aunt (the dead Tsarevich Aleksey’s half-sister) Elizabeth, Peter I’s daughter, another new Court coterie invited Peter I’s niece, Anna Ivanovna, a Baltic German and the widowed Duchess of Courland, to take the Throne. When the childless Anna died in 1740, she had appointed her infant nephew Ivan VI as her successor, with his mother Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna acting as Regent, but in 1741 Elizabeth Petrovna finally rose to the occasion to claim what many saw as her long-awaited rightful inheritance, deposing the boy emperor and his mother in a largely bloodless palace coup. Elizabeth ruled capably (if somewhat indolently) for 21 years, expanding Russian territory westward and southward and smashing Frederick II “the Great” of Prussia’s forces, before dying childless at Christmas 1761, leaving her hated, childish, temperamental, pro-Prussian, unpopular nephew as Emperor Peter III (from Schleswig-Holstein) and his popular, astute, savvy German-born wife Catherine as empress consort.

Less than eight months into his politically disastrous reign – during which time Peter managed astonishingly to alienate almost every powerful elite noble faction, offended the Orthodox Church with his Lutheran sympathies, and outraged Russian army officers and courtiers by returning most newly-conquered land to Prussia – Peter fatally and tactlessly made clear his intention to divorce the popular Catherine and marry his mistress. Catherine followed Elizabeth’s example and raised a small army of her supporters in a well-organised palace coup, ousting her feckless husband, and proclaiming herself as Empress regnant. Given that Catherine was not by blood a Romanov or even remotely Russian, this was a remarkable, unprecedented development for her to dare to do this, and speaks to her effectiveness as both a politician and a coup planner. Rather than acclaiming her young son and Peter III’s heir the Tsarevich and Grand Duke Paul as Emperor and she, Catherine, governing on his behalf merely as his Regent until he attained his majority, she was intent –her coterie of armed supporters just as much as she – on taking the supreme autocratic power for herself.

Paul and Catherine’s relationship

It is well known that Emperor Paul despised his mother Catherine II “the Great” because she kept him isolated, frustrated, and indolent away from her Court, viewed him as a political threat, took numerous male lovers (some of whom were much younger than him!), and treated him coldly. The Grand Duke was particularly outraged that his mother planned before her unexpected death in November 1796 to bypass him in the succession, excluding him in favour of his eldest son, her favourite grandson, the future Emperor Alexander I. In her Memoirs, Catherine also publicly claimed to have conceived Paul in 1754 out of wedlock by her first admitted lover, an imperial regiment officer Sergey Saltikov, openly alleging Paul to be both illegitimate and also, biologically, not a full Romanov. Most historians have argued due to their strong physical and temperamental resemblance that Paul was undoubtedly Peter III’s son by Catherine, despite her insinuations to the contrary. Catherine’s only real possible evidence-based claim to argue for Paul’s illegitimacy was the popularised account that at the time of their marriage, her temperamental, rather bizarre husband – like France’s dauphin, the future King Louis XVI – suffered from possible phimosis, and was thus incapable of a normal sex life until he underwent a medical procedure, most likely partial or full circumcision.

After a remarkably successful reign of 34 years, Catherine died (rather ignobly, of a stroke while on the toilet in her boudoir) before she could actually formally disinherit Paul. It comes as little surprise that one of Paul’s first acts as Emperor, to underscore his own legitimacy as his official father’s actual son (which he strongly believed himself to be) was to order his mother buried right alongside her long-dead, hated husband whom she had overthrown and whose murderers she had never punished 34 years earlier. Thus, Paul had his official parents, who had so despised each other in life, made to lay together eternally in death.

Catherine despised her first-born son because 1) Paul was, by custom and almost all interpretations of established royal and imperial primogeniture inheritance laws, the legitimate heir to his father’s usurped Throne which she unlawfully occupied, 2) he reminded her of his official (and almost certainly biological) father, her late husband and predecessor on the throne, Emperor Peter III, whom she overthrew and deposed and whom her supporters murdered in 1762, and 3) temperamentally Paul was much like his official father Peter, whom Catherine loathed, as both contemporary reports and her Memoirs affirm.

What the Pauline Succession laws meant for imperial women

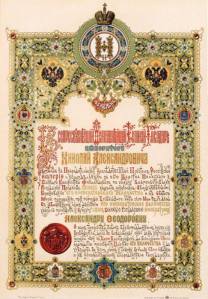

Paul’s succession changes —promulgated in April 1797 on the day of his and his Empress Maria Feodorovna’s joint coronation in Moscow — did not stipulate that no woman could ever inherit the Russian Throne and become the monarch. Rather, the Pauline Laws sought to establish an orderly and stable rule of succession to the imperial throne in the wake of what had, until then, been a preceding 75 years of intermittent succession crises and palace coups. The new laws established that following normal male-preference primogeniture, all living male dynasts (legitimate male relatives of the monarch) were to inherit the Throne in order of senior kinship relation to the monarch, and, only then, in default of any surviving male dynasts, the monarch’s female heirs (any daughters).

It is crucial to understand that the Pauline succession laws, adopted as the Imperial Succession laws of the House of Romanov, are not a Russian importation of Salic Law (which completely bars female succession) via royal France. Nor did Emperor Paul adopt these laws simply because he hated his mother. Catherine II was a brilliant empress in many ways, who presided over numerous much-needed administrative reforms, re-codified Russian law, endowed the Smolny Institute for girls and numerous other educational institutions and academies, and expanded Russia’s Empire west into Poland and south to the long-awaited Crimean Black Sea coast, with this making possible the dream of the “Greek project”; the eventual liberation of Constantinople from the Ottoman yoke. Yet, it remains indisputable that, hand-in-hand with these titanic accomplishments, Catherine was also a serial adulterer (as was her husband, and as were most male monarchs before and after her), indirectly a husband-killer and a regicide, and, most obviously, a usurper by the most basic definition of usurpation.

Catherine II was all these things, yet she is rightly termed ‘the Great’; yes, she continued culturally Westernising Russian elites, in the process cementing Peter I’s rending of the Francified Russian court and nobility from the more organic, traditional cultures of the Russian narod, but she was far more diligent to the mundane business of ruling the Empire than Elizabeth had been, far less violent in her policies and reform-minded approach to governing than Peter I, and far less eccentric, tyrannical, or despotic in her personal temperament than either Ivan IV, Peter I, or Anna. It is particularly worth noting that despite her personal flaws as an adulterer and deposer of her husband, rather than oppose her, the heart and centre of Russian history and cultural identity, the Orthodox Church, chose to crown and anoint her as empress regnant in her own right rather than accept her only as Regent for her son Paul, the lawful heir to the murdered Emperor Peter III. The Church’s active participation in the sacralisation and, therefore, political legitimisation, of a woman who was by the most basic definition of the term a usurper stands out here as a remarkable moment of tacit approval for actions which, on their face, seem to violate both established Church norms of personal conduct as well as monarchical principles of theoretically orderly succession. Yet, once the Church’s metropolitan had given her the crown to set on her own head, and then with chrism and public oaths sacredly anointed and blessed her rule, like it or not, courtiers and churchmen alike had to accept Catherine’s accession to the supreme power as a fait accompli; as Shakespeare observed in Richard II (Act 3, scene ii), “not all the rough water of the rough rude sea can wash the balm off from an anointed king”.

The Orthodox sacramental, theological, and mystagogical significance of crowning, anointing, and communing women in the clerical manner

Since time immemorial, the coronation and anointing of an Orthodox monarch by the Orthodox Church has been popularly and officially understood as a high mystery or sacrament of the Church, a divine charism and manifestation of God’s grace which confers real spiritual strength, healing, fortification, blessing, and illumination on the person being crowned and anointed. These spiritual realities are ubiquitously present throughout the coronation prayers, from the very beginning of the ceremonies at the narthex/vestibule and the western door, to the concluding prayers of thanksgiving and rejoicing at the end of the post-coronation Divine Liturgy itself.

As many Russian saints have observed (as recently as St John the Wonderworker of Shanghai and San Francisco), the coronation ceremonies are understood as a sacrament just as communion, confession and absolution, baptism and chrismation, and marriage are. This sacrament is ‘set apart’ from the others not by any set of exclusive rubrics or any official hierarchical downgrading or upgrading of its classification, but merely by its inherent and implicit uniqueness and exceptionality. Any and most Orthodox men and women do marry, do baptise, do make confession, but there is only one monarch, and therefore, in each reign, one coronation and anointing. This exceptionality is a positive one in that it serves to confer, project, and manifest the transferring of sacred authority and divine blessing – and with these, a political mandate to rule – onto and to one person and his/her consort.

Yet, in terms of the ‘salvific’ purpose of the coronation rites, the sacrament is truly universal in the sense that the coronation and anointing prayers serve to create and establish a covenantal relationship between God, the ruler, and the people, a three-way, mutually beneficial, solemn and sacred trust. This trust, naturally, extends beyond the realm of the Church and her faithful laity to include any and all non-Orthodox and non-Christian subjects of the monarch living under his or her jurisdiction and authority: thus, the monarch will ultimately have to render before God an account not only of his or her stewardship of the Christians in his realm generally, and the Orthodox ones in particular, but his stewardship, careful administration, and deliverance of justice and maintenance of peace for his non-Orthodox subjects.

Thus, the coronation of an Orthodox monarch is the Church’s highest form of publicly and sacredly obliging the new sovereign to care for all his or her subjects; in fact, symbolically and ritually, it binds the new monarch in sacred oaths to govern all his or her peoples as justly, fairly, and benevolently as possible. This is why, although traditionally Jews and Muslims are forbidden by their own laws and customs from entering a Christian sanctuary – since Christians are considered to practice shituf or shirk, a form of imprecise polytheism that conflicts with the Islamic concept of tawhid and the Jewish one of God’s absolute modal oneness – after the Orthodox coronation ceremonies, the new emperor or king would always make time to receive the accolades, well-wishes, and oaths of allegiance from leading representatives of his non-Orthodox subjects in an adjoining hall or palace room.

The Church’s role in the physical process of blessing, sacralising, and legitimising the rule of a new king, queen, emperor, or empress is undeniable, and ubiquitous throughout the coronation rites: the rites are performed in the realm’s paramount Orthodox cathedral, presided over by the realm’s senior Orthodox clergy, with all senior representatives of ecclesiastical and lay civil and religious life present to signify their assent and agreement. It is, after all, in Eastern Roman/Byzantine imperial practice – which all Orthodox realms consciously strove to imitate in their own coronation rites – the presiding bishop of the Church, the patriarch or metropolitan, who personally anoints the new monarch, and who usually physically crowns the monarch (or, in the post-Elizabethan tradition in Russia, presents the imperial crown to the monarch who then places the crown on his/her own head). Even in the most autocratic of political interpretations of the latter Russian development, the monarch still receives the crown from the hand of the ruling primate of the Church rather than from a lay nobleman.

My earlier article on the crowning and anointing of Russian empresses (both regnant and consort) was not intended to argue that women should not, could not, and ought not to be crowned as Orthodox monarchs, but rather that it was immensely significant that — beginning with Catherine I’s coronation and anointing as empress consort in 1724 at her husband Peter I’s insistence, through to 1762 when the Church crowned and anointed Catherine II, Russia’s last (as of yet) empress regnant — the Church actually not only crowned and anointed but also communed these ruling empresses, as She would do for all (post-1762) further empresses consort of Russia. Further, all Russian empresses regnant beginning in 1730 with Anna Ivanovna (who was, by all accounts, ironically a cruel tyrant in her temperament) communed of the Eucharist at their coronations behind the iconostasis in the altar, the most sacrosanct and holy area usually completely forbidden to most laymen and all laywomen (unless, in modern times, for instance, a priest or bishop was ill or dying in the altar and the only doctor present in the temple was a woman).

Iconographically, the reality that newly-crowned and anointed empresses regnant communed in the altar area surrounded by the all-male clergy is a crucial distinction and development of real theological importance with impossible-to-ignore implications. It shows that the Church, on the day of a woman’s coronation as empress regnant, was treating her identically to any male emperor or tsar; by allowing her to touch the Eucharist and commune herself at the altar with her own hands in the clerical manner, the Church on this occasion proclaimed her, a woman, to be not only an icon of Christ but an absolutely legitimate bearer of sacred royal authority and kingship as much as any male emperor. By virtue of allowing her to commune at the altar in the priestly, clerical manner – receiving the Holy Gifts in her hands rather than orally on a spoon from the chalice, as the laity do – the Church accepted that the quasi-sacerdotal role of ostensibly male kingship could indeed pass through and to a woman.

That the symbolic pinnacles of the coronation service itself – the physical crowning of the new monarch, his or her anointing by the primate, and, then, his or her solemn communing of the Eucharist at the altar in the clerical manner – were all celebrated and observed regardless of the monarch’s sex shows that, at a sacramental level, the Orthodox Church was blessing the direct participation of an extraordinary woman, a female monarch, in rites which carried an undeniably priestly role. Thus, rather than the monarch being permitted to commune at the altar because he was a male and, iconographically, was therefore naturally placed in a (male) priestly role as chief intercessor for his people before God, the reality of female monarchs communing in this way at the altar requires a different explanation. The Church must have understood the new monarch – regardless of sex – participating in the Eucharist, communing of the Lord at the altar, as a symbolic and mysterious moment of supreme sacralisation and conferral of the exceptional status of the monarch. No other Orthodox person, even the imperial consort, is permitted to literally touch God – in the Eucharist – with his or her own hands. Thus, the communing of himself or herself of the Eucharist by his or her own hands is, rather than a male sacerdotal function, a manifestation and realisation of the supreme, otherworldly, priestly dignity of kingship – or, more accurately here, sovereign power and supreme authority by the grace of God.

Having earlier in the coronation rite received the heavenly and divine authority to rule his or her people for their corporate benefit as God’s humble steward, and the chief defender and protector of the Orthodox Church and its Faith, the monarch now – in the most intimate and sacred moment of his or her lifetime – receives God Himself directly into his or her own hands, literally touching the Lord and feeding Him to himself or herself with his or her own hands. This most intimate of acts for the Christian, by which he or she communes of the Lord Himself, is in this moment the indwelling of Christ into the very mouth, body, and veins of the new anointed servant of God. The monarch, in this moment, communes in the understanding that the ‘bread’ and ‘wine’ he or she is imbibing are, in the spiritual and metaphysical sense, actually Christ’s own Body and Blood.

It is in this moment that the ‘exclusivity’ of male and female falls away; just as Christianity has always insisted that men and women are spiritually equal before God, with each soul created after the divine image, in this most unique of unique circumstances – the communion of the Body and Blood by the newly crowned and anointed monarch – a female monarch is just as much a person set apart in a sacerdotal calling, a priestly Davidic calling of kingship and sacred rule, as any male monarch. This is why – on this singular occasion at the climax of the Divine Liturgy immediately following her coronation and anointing – an empress regnant communed in the same manner as did male monarchs and, more importantly, the Church’s bishops and priests. While this obviously did not and does not automatically and logically translate to the Orthodox Church believing that women can and should be ordained as priests, what it shows is that in the instance of the coronation of a monarch, theologically the Church sought to confer the same blessing and sanctity on a female monarch as it did to a male monarch, making no distinction in how a female monarch would commune of Christ’s Body and Blood immediately following his or her anointing.

The uncertain position of the Russian Church on the coronation of women before Catherine I

Prior to 1724, the Russian Orthodox Church had not established a solid precedent of permitting the crowning of a Russian tsar’s consort as tsaritsa in an Orthodox ceremony universally recognised as legitimate. Upon Tsar Fyodor I’s death without issue in January 1598, his widow Tsarina Irina Godunova evidently had the opportunity to become the reigning sovereign in her own right, as the direct Rurikid male line had now become extinct; some accounts thus refer to her retirement to the Novodevichy Monastery as an abdication, following which her brother Boris Godunov was duly informed of his election and appointment as tsar by Patriarch Job and the Zemsky Sober (“Assembly of the Land”).

During the “Time of Troubles” after Tsar Boris I’s death in April 1605, shortly before his murder, the Polish Roman Catholic imposter/usurper the “False Dmitry” insisted on having his wife Marina Mniszech crowned and anointed as Tsaritsa in May 1606 in an ostensibly Orthodox ceremony. The coronation, presided over by Patriarch Ignatiy (Ignatius), was of dubious legitimacy since Ignatiy was never universally recognised as primate by the Orthodox. This was because Dmitry (or his supporters) had installed in June of 1605 after rather irregularly removing his predecessor, Iov (Job).

Despite the apparent legitimacy that this coronation would, on its face, seem to confer on Marina, there is no evidence that she ever embraced Orthodoxy, so this factor, along with her Polish ethnicity and status as the hated Dmitry’s wife, may have served to render her illegitimate in the eyes of most of Moscow’s population. The question of the legitimacy of her status as Russia’s first crowned and anointed tsaritsa is further complicated due to Patriarch Ignatiy’s eventual deposition following the False Dmitry’s murder, and the former’s subsequent embrace of union with Rome. Because of these factors, the Orthodox usually view Ignatiy as a Catholic Polish puppet and thus omit him from the register of Russian patriarchs. At the time of Maria’s coronation by Ignatiy, he was not yet in communion with Rome and technically, due to Job’s forced exile, the only reigning Russian hierarch resident in Moscow. Yet his open support for Dimitry’s cause provoked considerable opposition from many of the other Russian hierarchs who, like Job, refused to recognise Dmitry as a legitimate tsar (and thus Maria as tsaritsa and Ignatiy as patriarch).

Eastern Roman (“Byzantine”) theological and political precedents in the coronation of empresses regnant and consort

That the Orthodox Church in Russia should have objected to crowning its male monarchs’ female consorts is rather odd, since Eastern Roman/Byzantine imperial practice which so strongly influenced Muscovite Court ceremonial, conscious political identity, and religious ritual did have the custom of the Patriarch of Constantinople crowning and anointing the emperor’s wife as empress (consort). Despite the precedent of the Constantinopolitan Church crowning the imperial consorts, it is worth noting that the few imperial women who ever briefly ruled Constantinople as empresses regnant were never crowned as such in their own right; rather, these women were crowned and anointed as consort when their husbands were still alive, as happened with Catherine I of Russia (who was never crowned as empress regnant following her assumption of the Russian Throne at Peter I’s death).

Some historical revisionists without firm theological foundation in Orthodoxy have sought to argue that the figure of the Virgin Mary/Theotokos/Bogoroditse/Miter Theou/Bogomater can be used to justify and legitimise female monarchs ruling from a Christian theological perspective. The problem with this argument is that literally no Orthodox or Catholic saints or any authoritative writings view the Virgin Mary as a kind of ruling heavenly monarch; she is understood as the Queen Mother of Heaven, not a ruling monarch in any way — she reigns in glory and majesty but does not rule; her Son rules, and will ultimately judge, in Orthodox eschatology, sitting as King on His Father’s throne. Christ’s Mother’s eternal, blessed role is that of heavenly supplicant, intercessor, “steadfast protectress and constant advocate” on behalf of the faithful before her Son, a role which numerous Late Antiquity, medieval, and early modern Christian princesses and queens consort sought to follow and emulate, interceding for mercy before their husbands, fathers, or sons on behalf of the poor, the imprisoned, or the condemned. Stony Brook University Russian history professor Dr. Gary Marker explains these highly gendered conceptions of kingship, consort queenship, authority, and clemency at length in his superb book Imperial Saint: The cult of St Catherine and the dawn of female rule in Russia.

Thus, the theological precedents and justifications for female rule in the Orthodox understanding cannot be based on the Theotokos (there is literally no evidence to support such claims), but rather more selectively on the Old Testament biblical judge Deborah, and to a much lesser extent on the widowed warrior Judith. We have evidence that Christian royal court poets, feast and pageant planners, coronation chroniclers, etc. conceived of and explained the exceptional phenomenon of women ruling as monarchs using these exceptional biblical figures. All the queens mentioned in the Old Testament were either lauded as righteous, pious consorts, brave protectresses and advocates who defended the Israelites from their enemies (Persian Jewish queen consort Ester), or demonised as treacherous, evil whores and murderesses (Jezebel and Athaliah). The Hasmonean Salome Alexandra (שְׁלוֹמְצִיּוֹן אלכסנדרה, Shelomtzion or Shlom Tzion) was the only queen regnant of Jerusalem, though she was not universally acknowledged as such, with some viewing her instead as a particularly capable regent.

Numerous medieval western Christian kingdoms did have female monarchs, some of whom were very capable and successful, but it serves little purpose to a try to anachronistically superimpose modern-day feminist and revisionist interpretations of how Christians viewed someone such as the Virgin Mary in desperate hopes of finding (or conjuring up) unreliable evidence to try to support dubious new interpretations. Put simply, it is appallingly bad, prejudicial history which subordinates and manipulates any evidence to an already – sought after, predetermined ideological end or purpose.

While the Byzantines/East Romans did have several empresses regnant — only five from 330-1453 — none of these women ruled as monarch for more than a few years, similar to the “caretaker”/transitional roles of the handful of ancient Japanese empresses regnant. The imperial Roman Augusta (feminine of Augustus) widely considered to be Late Antiquity’s first Empress regnant was St. Pulcheria, who governed the Eastern Empire for over 30 years for her brother Emperor Theodosus II as the first official woman Regent in Roman history. A devout orthodox/catholic Nicene Christian, she kept a high degree of personal autonomy and independence by taking a vow of chastity and celibacy. Only when Pulcheria’s brother died childless was she proclaimed as the reigning empress, and then she immediately undertook, while still remaining a virgin, to marry the general Marcian in order to secure much-needed political and military support and solidify her rule. A dedicated opponent of Nestorius, she convened the 451 Council of Chalcedon. She died only a few years later and her nominal consort (de facto co-ruler) Marcian actually remained as the monarch until his own death (essentially having obtained the Crown Matrimonial as Lithuanian duke Władisław Jagieło did upon marrying Poland’s reigning Queen St. Jadwiga, who predeceased him).

St. Justinian the Law-giver’s actress-courtesan-turned-Empress St. Theodora; unofficially they can in some ways be considered de facto co-rulers, but she was never formally proclaimed as such. Irene of Athens (r. 797-803) was an empress consort and then dowager and Regent who seized the throne by blinding her own son when the young Emperor sought to assert his own authority apart from her. Then the Macedonian dynasty’s last two reigning monarchs, the imperial porphyrogennetai Zoe and Theodora stand out; Zoe ruled alongside three successive husbands who actively co-ruled with her, while Theodora was around 70 and childless when Zoe died and she finally ruled as monarch for several years. These few women were either able rulers (Pulcheria and the last Theodora), or made infamous by Eastern Roman chroniclers as the epitome for why Christian women should not rule empires (Irene). The Church either actively blessed or at least tolerated all these women as monarchs who ruled briefly, but there is not a single instance in Byzantine history in which a woman ruled for many years (e.g. a decade or more) as empress regnant.

From the first Catherine to the second: the Russian Church’s coronation and anointing of four empresses in less than forty years (1724-1762)

Why was Catherine I never crowned as monarch after her unexpected accession in 1725? Perhaps 1) since she died only two years later, this was before it could be properly planned and adequate funds set aside, 2) she and her advisors thought that her anointing and expensive, popular 1724 coronation as empress consort still sanctified and blessed her to rule after Peter I as monarch, or 3) the Church was not yet ready to crown a barely literate Livonian peasant woman, former Lutheran, and former Army colonel’s mistress, Marfa Skavronskaya, as monarch, though of course she had converted to Orthodoxy and taken the name Catherine when she married Peter I.

What is remarkable and astonishing is how rapidly the Church went from reluctantly allowing Peter I to crown his wife Catherine as the first Orthodox woman anointed and crowned as the imperial consort with the Church’s full cooperation and public blessing in 1724, to in 1730 fully blessing the Baltic German Anna Ivanovna’s coronation and anointing as Russia’s new, second empress regnant, even allowing her to commune at her coronation in the altar like a priest or bishop. What is especially fascinating is that neither Peter I nor any of his male predecessors as tsar seem to have communed in the altar at their coronations, or, if they did so, this was evidently such a routinely observed or normative, prevailing coronation custom as to go without commentary or remark in any period chronicles. What we do know for certain is that there is no evidence available indicating that Catherine I communed at the altar at her coronation, but rather, it seems likely that she communed in the lay manner, as all future empresses consort would do, on the solea, being the first of the laity to receive communion.

Thus, it is entirely plausible that the first Russian monarch, male or female, to commune at the altar in the clerical manner was actually Anna Ivanovna, a dour, temperamentally unstable Baltic German princess who was by no means the universally acknowledged rightful heiress in 1730 (the rightful heir to the childless and heirless Peter II, being, according to primogeniture, his half-aunt Elizabeth Petrovna, Peter I’s daughter by Catherine I). Thus, while all male Russian emperors beginning with Paul I received communion at their coronations at the altar, in the clerical manner, we know that this practice was first definitively observed at the coronation of a widowed Baltic German woman as sole empress regnant in 1730.

My brief article (published in September 2015) which goes into more detail regarding the coronation ceremonies themselves: http://www.pravoslavie.ru/english/80559.htm

Sources:

Bogdanow, A. “Russkije patriarchi. Snizchoditielnyj Ignatij”. krotov.info (in Russian). Retrieved 2012-05-01. Accessed 2016-09-07.

Horan, Brian Purcell. The Russian Imperial Succession. RIUO.org. http://riuo.org/RussianImperialSuccession/russianimperialsuccession.html

McGrew, Roderick E. Paul I of Russia: 1754-1801. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992.

Meehan-Waters, Brenda. “Catherine the Great and the Problem of Female Rule”. The Russian Review, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Jul., 1975), pp. 293-307. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/127976?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Nikolaieff, A.M. “Boris Godunov and the Ouglich Tragedy” Russian Review 9, No. 4 (1950), pp. 275-85.

Succession to the Imperial Throne of Russia. Fundamental Laws. Ed. Antony, Archbishop of Los Angeles and South California. Order of the Imperial Union of Russia, Bridgeport, Connecticut, 1984.

Thyret, Isolde. “‘Blessed is the Tsaritsa’s Womb’,” 479-96; Idem, Between God and Tsar. Religious Symbolism and the Royal Women of Muscovite Russia. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2001.

Zenkovsky, Sergey. Medieval Russia’s Epics, Chronicles, and Tales. New York: Meridian Books, 1974.

Zhmakin, V.I. “Koronatsii russkikh imperatorov i imperatrits 1724-1856 gg.”, (“Coronations of Russian emperors and empresses”), Russkaia Starinaissue 37, 1883, pp. 500, 517, and 522.

Partners in holy and royal matrimony and equal bearers of the burden of imperial rule, Emperor Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra are here shown sketched as they leave the Uspenskiy Sobor in full regalia following their coronation and anointing.